As I write bite-sized bios of my great-grandparents, who died long before I was born, I find I'm curious about their daily lives.

For instance: Did great-grandma Leni Kunstler Farkas (1865-1938) and great-grandpa Moritz Farkas (1857-1936) become fluent enough to speak, read, and write in English?

Both were born in Hungary (in an area now in Ukraine). Both were, I'm confident without any real proof, able to read and write in their native Hungarian language. Why? Because Leni was the daughter of a family that owned property and operated an inn...Moritz supervised his in-laws' vineyard and leased lands to farm. They interacted with officials, not just family members, and would have needed some level of proficiency in Hungarian.

Comparing family stories and research

Research and family stories agree on many aspects of these immigrant ancestors' lives. Moritz arrived in New York City in August, 1899, Leni arrived in November, 1900, and their Hungarian-born children followed in two waves. Moritz worked as a presser and cloak maker within the New York City garment industry. Leni was in charge of their children and ruled the household.

The youngest kids went to city public schools and picked up English quickly and naturally. The older children (mid-to-late teens) worked during the day and went to night school to learn English. At the end of the work week, they handed their pay packets to Leni. She doled out carfare and lunch money for the next week, and kept the rest for rent, food, and other expenses (including an occasional summer getaway of her own, according to family lore).

Both Leni and Moritz lived in New York City for three decades. Moritz worked outside the family, while Leni may have had dealings with landlords, shopkeepers, school officials, and others in the neighborhood.

But how well could they speak, read, and/or write English? My oldest cousins, who were toddlers when these ancestors died, have distant memories that could only be based on actual conversations, in English, with Leni and Moritz. What other clues can I gather?

Start with the US Census

My first step was to return to the US Census, which often asked about proficiency in English. Interestingly inconsistent answers!

- 1900 Census: Moritz lived as a boarder in someone else's Lower East Side tenement apartment. For the question "speak English?" the enumerator had originally written YES but overwrote it and the answer is illegible.

- 1910 Census: YES, Moritz can speak English, according to this record, but NO, Leni's answer is "Magyar."

- 1920 Census: NO, neither Moritz nor Leni is recorded as being able to speak English. Their native tongue is "Jewish," according to this Census.

- 1930 Census: YES, both Moritz and Leni are recorded as being able to speak English. The language spoken at home before coming to America is listed as "Magyar."

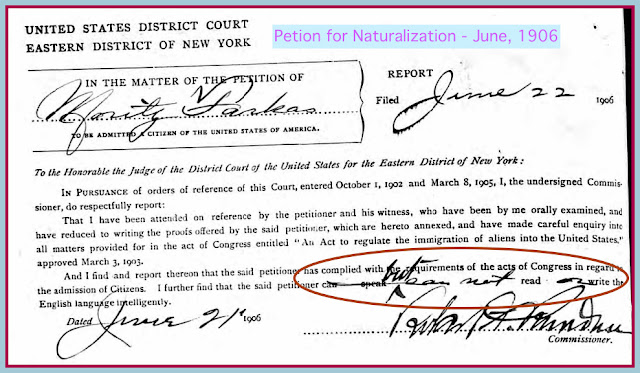

Next stop: naturalization documentationNext, I looked at Moritz's Petition for Naturalization, dated June of 1906. He had been in America for nearly seven years at that point.

As shown at top, the commissioner who signed this petition indicated that no, Moritz could NOT "read or write the English language intelligently."

So...yes or no?

My conclusion, based on this research, is that for the first decade in America, neither of these ancestors could do more than understand a bit of basic English and possibly answer with a stock phrase.

I believe, based on my research and my cousins' dim memories, that eventually, both Leni and Moritz understood spoken English fairly well, and could converse in English with people outside the family, even if their vocabulary was not extensive or sophisticated.

I doubt either ancestor could read or write very much English by the time they passed away. Most likely, they (like so many immigrants) relied on their children all their lives to be interpreters and read/write English when necessary.

-- This is my post for week 4 of Amy Johnson Crow's #52Ancestors series, with the theme of "curious."